I am of the opinion that the alleged gulf between art and science is not only exaggerated but to a large degree a mere legend. Notwithstanding the high degree of specialization and training required of a contemporary scientist, which makes being a Renaissance man or woman a real challenge today, or the way education systems often force young people to chose one path or the other, we find artists involved involved in science in roles ranging from enthusiast to professional researcher producing peer reviewed studies. This has long been true and is reflected often in their art. Usually I write about the intersection of visual art and science. Today I want to look at writers of literature and science. The very concept of a 'scientist' is quite modern, and if we look back more than a couple of centuries, thinkers were thinkers and generally did 'all of the above'. Natural philosophy was rarely if ever a full-time gig. Even if we restrict ourselves to the era after the term 'scientist' was coined (by Whewell, initially in 1834), it's not hard to find a rich and fascinating intersection between the worlds of science and literature, beyond the obvious areas of science fiction or popularization of science. As Vladamir Nabokov wrote, "Does there not exist a high ridge where the mountainside of ‘scientific’ knowledge joins the opposite slope of ‘artistic’ imagination?”

No less a writer than Charles Dickens corresponded with the great physicist and chemist

Michael Faraday in 1850. Dickens wanted Faraday's Royal Society Christmas Lectures of 1848,

Chemical History of a Candle, to be adapted for his weekly journal

Household Words. Dickens wrote to Faraday that ‘it occurred to me that it would be extremely beneficial to a large class of the public to have some account of your late lectures on the breakfast-table…and (for) children.’ Faraday agreed, and Dickens assigned his friend Percival Leigh to write the adaptation. Dickens' interest in chemistry can be seen in his Christmas tale,

A Haunted Man, written in 1848, in which a phantom appears to a chemist, 'a learned man in chemistry…surrounded by his drugs, instruments and books among a crowd of quaint objects…glass vessels that held liquids…’ named Redlaw. In this Dickensian

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, the ghost offers Redlaw the ability to forget painful memories so long as he passes the gift on. Later, in

Our Mutual Friend (1864–5), Dickens likens a mysterious retainer to a gloomy analytical chemist. (via

Bill Griffith, Dickens and the Haunted Chemist, chemistry world)

Henry David Thoreau considered himself a civil engineer. He worked on a way to make pencils with inferior graphite, using clay as a binder, developed a new grinding mill, invented a pipe forming machine, and designed water wheels. (

via).

We would never have Lewis Caroll's Alice, without Charles Dodgson's mathematics.

Mark Twain participating in an experiment in Tesla's laboratory. Century Magazine, April 1895. Source:

peswiki.com

Literary giant

Mark Twain and Serbian-American inventor, engineer, physicist and futurist

Nikola Tesla became good friends and spent much time together in his lab and elsewhere.

"I had hardly completed my course at the Real Gymnasium when I was prostrated with a dangerous illness or rather, a score of them, and my condition became so desperate that I was given up by physicians. During this period I was permitted to read constantly, obtaining books from the Public Library which had been neglected and entrusted to me for classification of the works and preparation of the catalogues. One day I was handed a few volumes of new literature unlike anything I had ever read before and so captivating as to make me utterly forget my hopeless state. They were the earlier works of Mark Twain and to them might have been due the miraculous recovery which followed. Twenty-five years later, when I met Mr. Clemens and we formed a friendship between us, I told him of the experience and was amazed to see that great man of laughter burst into tears." — Nikola Tesla, Electrical experimenter magazine, 1919.

Twain had three patents of his own including an "Improvement in Adjustable and Detachable Straps for Garments" to replace suspenders, a history trivia game and a self-pasting scrapbook in which the dried adhesive on the pages needed only to be moistened before use. This third invention enjoyed some actual commercial success.

1 Thomas Edison visited Twain at home in 1909 and filmed him. Twain's interest in science and technology shines through in

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, where the protagonist time traveler tries to introduce contemporary technology to the Arthurian court. This of course spawned a whole sub-genre of later science fiction.

Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, with Poe on the right, Source:

brainpickings.org

Edgar Allan Poe spent time at the “Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia,” doing research on mollusks. He's shown at right in the Academy's building at Board and Sansom Streets during the winter of 1842-43. This daguerrotype, possibly by Paul Beck Goddard, is incidentally the oldest-known photograph of the interior of an American museum (via

Brainpickings). Poe was hired to write a preface and work on translating Cuvier's work on conchology from French into English. The work (

The conchologist's first book: a system of testaceous malacology, arranged expressly for the use of schools, in which the animals, according to Cuvier, are given with the shells, a great number of new species added, and the whole brought up, as accurately as possible, to the present condition of the science), written by Thomas Wyatt (with some text lifted from English naturalist Thomas Brown) was attributed to Poe, perhaps in the aim of attracting more sales. His own biographers accused Poe of plagiarism, seemingly embarrassed by his foray into natural philosophy, but modern historians of science see that Poe actually reorganized Wyatt's work, having learned from Cuvier that shell shape wasn't enough to classify mollusks and made genuinely useful contributions to the taxonomy of these creatures. (via the

Smithsonian Library and

Engines of our Ingenuity)

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) admires a catch aboard the Pilar, 1934. Source:

brainpickings.org

Ernest Hemingway whose passion for sport-fishing is well-known, was a later member of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. In 1934, the Academy's Managing Director Cadwalader asked for his aid for a research expedition to study the life histories, migrations, and classifications of Atlantic marlin, tuna, and sailfish, lead by the Academy's Chief Ichthyologist, Henry W. Fowler, in Cuban waters. The three of them spent a month aboard Hemingway's vessel, the

Pilar, catching, measuring and classifying fish. Correspondence between them after the expedition shows that Hemingway contributed to Fowler's ability to accurately classify the marlin of the Atlantic Ocean. (via

ANSP) Hemingway's love of fish and fishing are of course evident in the fishers in his stories, not least

The Old Man and the Sea.

Nabokov's drawing of a heavily spotted Melissa blue and the scale-row classification system he developed for mapping individual markings. Source:

brainpickings.org

Perhaps better known than Hemingway's contribution to ichthyology, is

Vladimir Nabokov's contributions to lepidoptery (or the study of butterflies). As well as writing and teaching literature at Wellesley, he worked as the

de facto curator of lepidoptery at Harvard University's Museum of Comparative Zoology, and in fact wrote

Lolita on butterfly-collection trips in the western United States each summer.

2 After these trips he published detailed descriptions of hundreds of different species. He wrote, "My pleasures are the most intense known to man: writing and butterfly hunting.”

3 Recently, research has shown that Nabokov's hypothesis that the American Polyommatus blues had evolved over millions of years of successive waves of emigration from Asia is true. His dissections and alternate classification methods based on their multifarious genitalia lead him to question the accepted relationships between species and even speculate that “a modern taxonomist straddling a Wellsian time machine,” would find only Asian forms of the butterflies existed millions of years ago, but that five waves of butterflies would arrive in the New World with advancing time. Kurt Johnson revived Nabokov's classification scheme in 2000, and with Coates wrote the book

Nabokov's Blues. The species

Nabokovia cuzquenha was named in his honour. His disputed claim that the rare Karner blue butterfly is distinct form Melissa blues has recently been supported by detailed DNA sequencing. Then in 2011, entomologists reconstructed the evolutionary tree of blues and found that Nabokov's emigration hypothesis was right and further that they emigrated as he imagined, via the Bering straight and then south. (

via NYT)

I started reading Jeanette Winterson after I heard her interviewed about

Gut Symmetries, which of course alluded to GUT (or Grand Unified Theories) symmetries in particle physics. Her 1997 novel about a love triangle, held together like quarks in a proton or neutron, plays on contemporary physics. She explained in the interview how her fascination with quantum mechanics and cosmology lead her to get a physics tutor and then write this novel. A.S. Byatt's novels are full of scientists doing actual science. In particular zoology, entomology, neuroscience and the theme of Darwinism are common. She's called herself a "failed scientist".

4 Unlike Keats who claimed science stole nature's magic, she told the Independent, "Science is now, and was even in Keats's day, revealing to us mysteries and miracles considerably greater on the whole than those invented by poets."

5 She explains that, "We have a moral responsibility to engage with science, we're destroying the natural world quite rapidly."

4 Author Alan Lightman of course, is a physicist (who works on theoretical astrophysics, General Relativity particularly under extreme conditions like accretion disks around blackholes). His most well-know novel,

Einstein's Dreams is very tied to physics - a sort of poetic and literary telling of relativity, time and fantasy.

Whether impelled by their sense of moral responsibility or sheer interest in the world around them, these authors have not only stayed abreast of their contemporary science, or communicated science elegantly, many of them have participated in the grand enterprise itself. After all, explaining the world is a variation of the process of writing; it's a function of observing closely, and telling stories. As scientists we of course must test our hypotheses, make testable predictions and ensure our hypotheses are consistent with all available data (requirements not explicitly made on the novelist), but at its heart, science is also about storytelling, both working to understand and working to explain: can we tell a self-consistent story about a given phenomenon? I don't think it's all that surprising that writers who care about people, the world and think closely about these things are also attracted to the natural world around them.

I stumbled upon this wonderful series of illustrations of the elements personified and excited to see they are now available as flash cards on Etsy, by San Francisco illustrator Kaycie D. She describes the project as 'Experiments in Character Design'. I would think this would make not only a lovely periodic table, but a really great way for students to familiarize themselves with the 'character' of different elements. Check out the first eight elements below.

I stumbled upon this wonderful series of illustrations of the elements personified and excited to see they are now available as flash cards on Etsy, by San Francisco illustrator Kaycie D. She describes the project as 'Experiments in Character Design'. I would think this would make not only a lovely periodic table, but a really great way for students to familiarize themselves with the 'character' of different elements. Check out the first eight elements below.

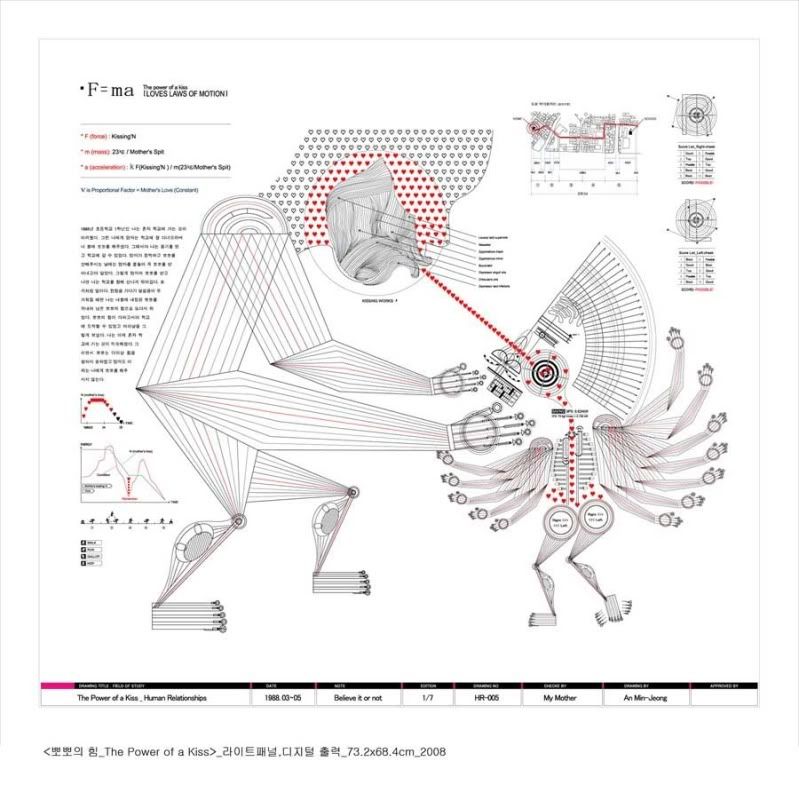

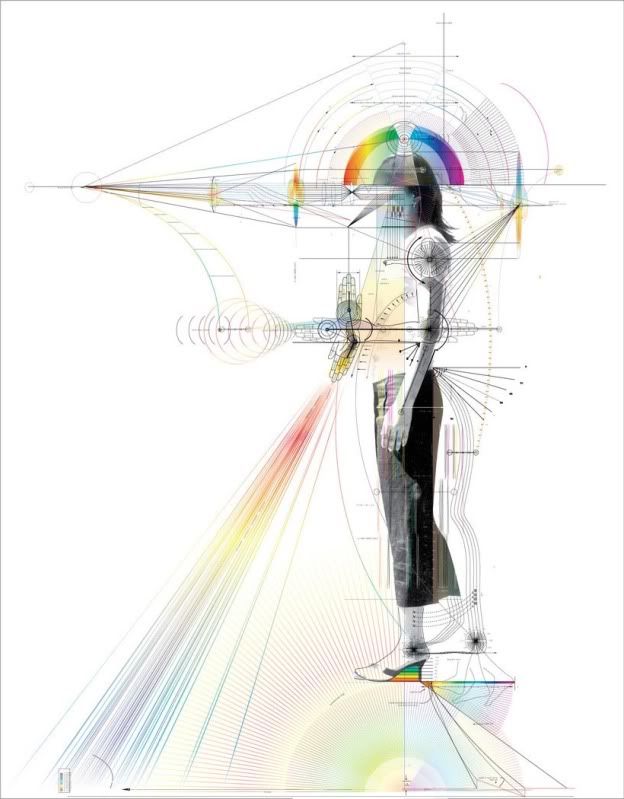

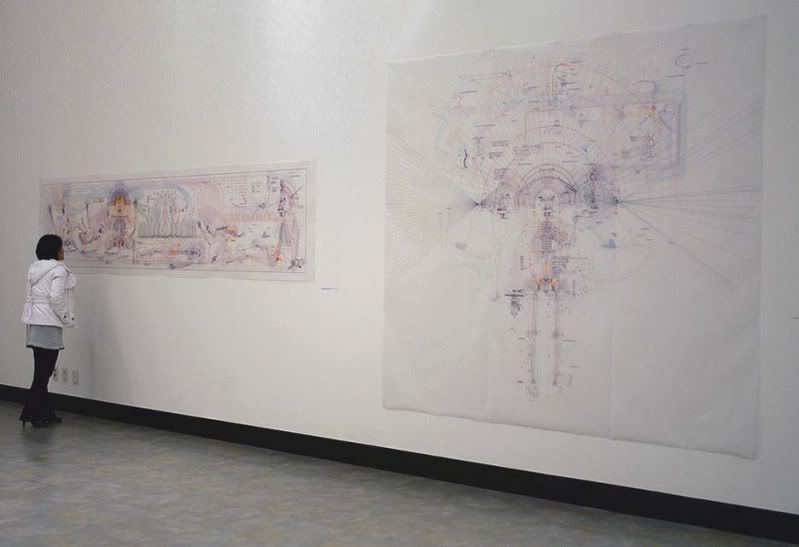

I've seen the staggering art of Korean artist

I've seen the staggering art of Korean artist