|

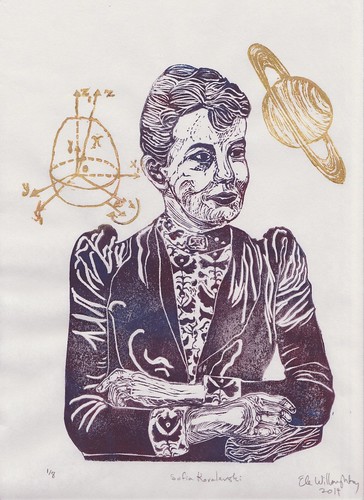

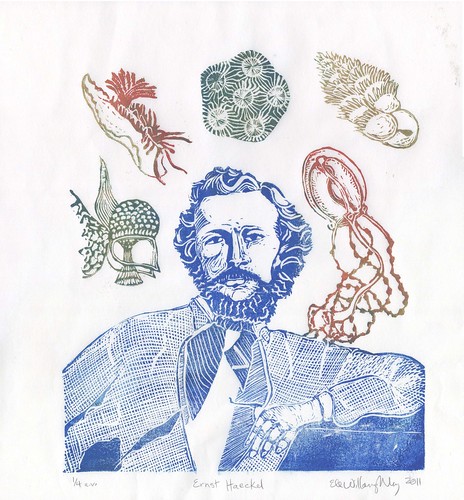

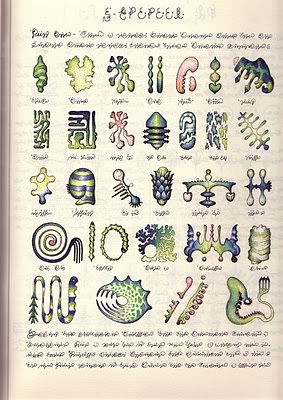

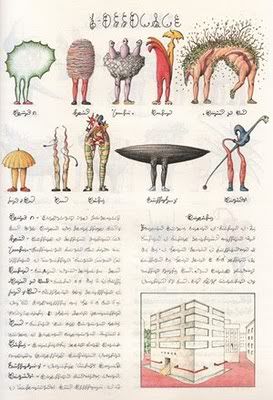

| Ursula Franklin, linocut, 11" x 14" by Ele Willoughby, 2016 |

This year, to celebrate the international celebration of the achievements of women in science, technology, engineering and math, Ada Lovelace Day (ALD16), I am returning again to my first subject: Ursula Franklin (16 September 1921 – 22 July 2016). Every year since 2009, people have devoted the 2nd Tuesday in October to blogging about (and otherwise celebrating) the under-recognized and under-appreciated women who have made pivotal contributions to STEM throughout history, in the name of Countess Ada Lovelace. (I hope you'll all recall, Ada, brilliant proto-software engineer, daughter of absentee father, the mad, bad, and dangerous to know, Lord Byron, she was able to describe and conceptualize software for Charles Babbage's computing engine, before the concepts of software, hardware, or even Babbage's own machine existed! She foresaw that computers would be useful for more than mere number-crunching. For this she is rightly recognized as visionary - at least by those of us who know who she was. She figured out how to compute Bernouilli numbers with a Babbage analytical engine. Tragically, she died at only 36.)

|

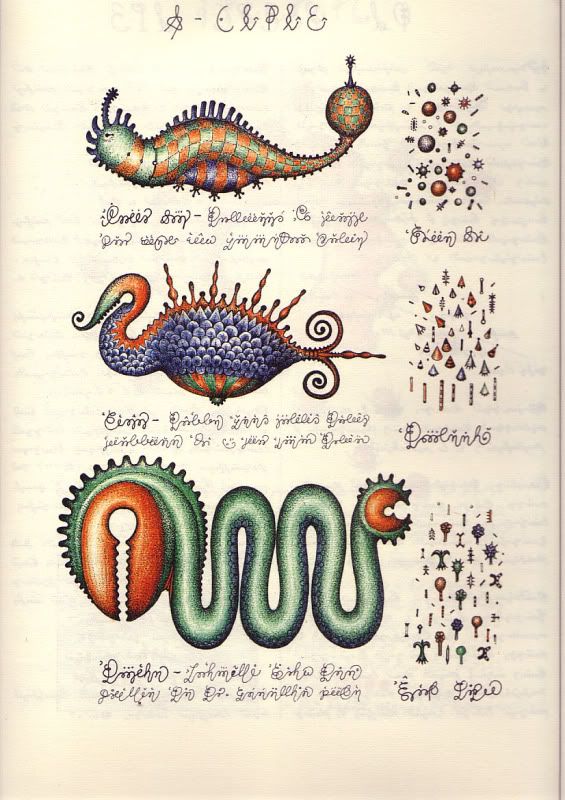

| A preliminary mock-up of one of the Phylo cards in this new Women in Science and Engineering set featuring my portrait of today's namesake: Ada Lovelace |

Franklin was born in Munich in 1921 and survived being interned by the Nazis. She received her PhD in physics from the Technical University of Berlin in 1948 and immigrated to Canada, where after a post-doc at U of T, she joined the faculty. She pioneered archeometry - the use of modern materials analysis in archeology, dating prehistoric artifacts made of metals and ceramics. In my portrait I include an image of an ancient Chinese ding vessel to represent both her metallurgical research and archeometry and her writing about "prescriptive" versus "holistic" technologies used in mass production versus technologies used by craft workers and artisans. Her science was always engaged with societal concerns. During the 60s she advocated for the atmospheric nuclear test ban treaty, citing her studies of strontium-90 radioactive fallout found in children's teeth. Strontium-90 (90Sr) is called a "bone-seeker" because biochemically it behaves like calcium and when absorb it in our bodies what isn't excreted finds its way to our bones. Thus, this radioactive product of nuclear fission (for instance, in atmospheric tests of nuclear weapons) is particularly dangerous and can cause cancers. It decays by beta decay, giving off electrons, as shown by the child's tooth in my portrait. During the 70s she was part of the Science Council of Canada investigation of how we could better conserve resources and protect nature. She began to develop her ideas about complexities of modern technological society.

She consistently has stood up for her beliefs in peace and social justice. As a member of the Voice of Women (now called Canadian Voice of Women for Peace), she tried to persuade Parliament to disengage Canada from supplying any weapons to the US during the Vietnam war, to shift funding from weapons research to preventative medicine, to withdraw from NATO and disarm. She later fought to allow conscientious objectors to redirect part of their income taxes from military uses to peaceful purposes (though the Supreme Court declined to hear the associated case). She joined other retired female faculty in a class action law suit against the University of Toronto for claiming it had been unjustly enriched by paying women faculty less than comparably qualified men. The University settled in 2002 and acknowledged that there had been gender barriers and pay discrimination.

As an applied scientist, her writings on technology benefit from the insight of an insider, but her priorities are justice and peace and she critiques and analyses technology in this light. She does not view technology as neutral; it is a comprehensive system that includes methods, procedures, organization, "and most of all, a mindset". It can be work-related or control-related, holistic and prescriptive. Franklin argues that the dominance of prescriptive technologies in modern society discourages critical thinking and promotes "a culture of compliance". She investigated the relationship between technology and power. She investigated how we interact with communication technologies and advocated for the right to silence - long before our contemporary concern with these issues.

Many of her articles and speeches on pacifism, feminism, technology and teaching are collected in The Ursula Franklin Reader (2006). A nod to her pacifism and feminism is built into the structure of her portrait which encompasses the symbols for peach and women in the negative space. Franklin is one of many respected scholars and thinkers to have delivered a series of Massey Lectures, in 1989. Hers were gathered and published as The Real World of Technology. She has been recognized for her work in many ways, including receiving the Order of Canada, Governor General's Award in Commemoration of the Persons Case for promoting the equality of girls and women in Canada and the Pearson Medal of Peace for her work in advancing human rights. She was inducted into the Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame in 2012. Locals may know the Ursula Franklin Academy, a Toronto high school, named in her honour. I think this University, city, country and in fact, society at large were made a better place because Ursula Franklin was a part of it. So, though she has received this recognition, I think she should be a household name, so that's why I am happy to add her to my portrait pantheon of scientists and write about her again this Ada Lovelace Day 2016. I also think that it is very apt to combine making her portrait using holistic technologies of the artisan and sharing it through more prescriptive digital technologies with the world.

(NB: much of the biographical information is recycled from my own previous post about Franklin) .