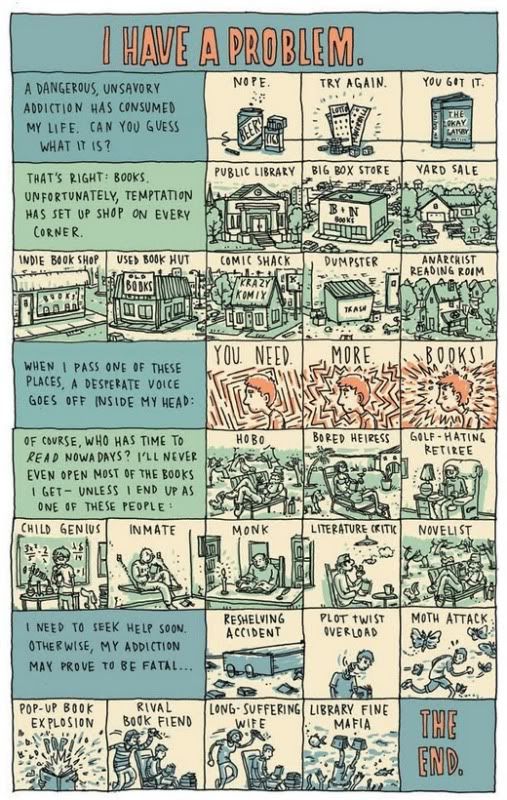

I seem to have fallen out of the habit of regularly reviewing books on my blog. I used to be more disciplined about it, and there is a series of reviews on the minouette blog (and here), including the one below for one of my favorite books of the last several years. I've also mentioned The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet on magpie&whiskeyjack, comparing the whimsical maps and scientific illustration of everything incorporated into the work of artist Simon Evans with those of the more strictly empirical modern-day Humboltian cartography protegy Spivet. If you, like me, are inspired by the fertile intersection of art and science, this is a novel for you. You should go read it right away, because as I was very pleased to read this morning, Jean-Pierre Jeunet (director of Amelie, or Le Fabuleux Destin d'Amélie Poulain in French) has adapted the novel for a movie to be released in France (filmed in English, with French subtitles) in October.

I seem to have fallen out of the habit of regularly reviewing books on my blog. I used to be more disciplined about it, and there is a series of reviews on the minouette blog (and here), including the one below for one of my favorite books of the last several years. I've also mentioned The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet on magpie&whiskeyjack, comparing the whimsical maps and scientific illustration of everything incorporated into the work of artist Simon Evans with those of the more strictly empirical modern-day Humboltian cartography protegy Spivet. If you, like me, are inspired by the fertile intersection of art and science, this is a novel for you. You should go read it right away, because as I was very pleased to read this morning, Jean-Pierre Jeunet (director of Amelie, or Le Fabuleux Destin d'Amélie Poulain in French) has adapted the novel for a movie to be released in France (filmed in English, with French subtitles) in October.The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet by Reif Larsen

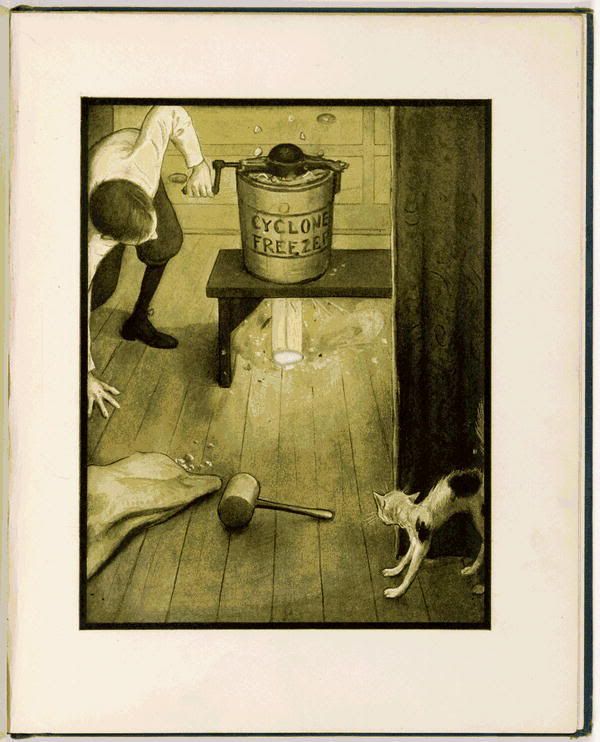

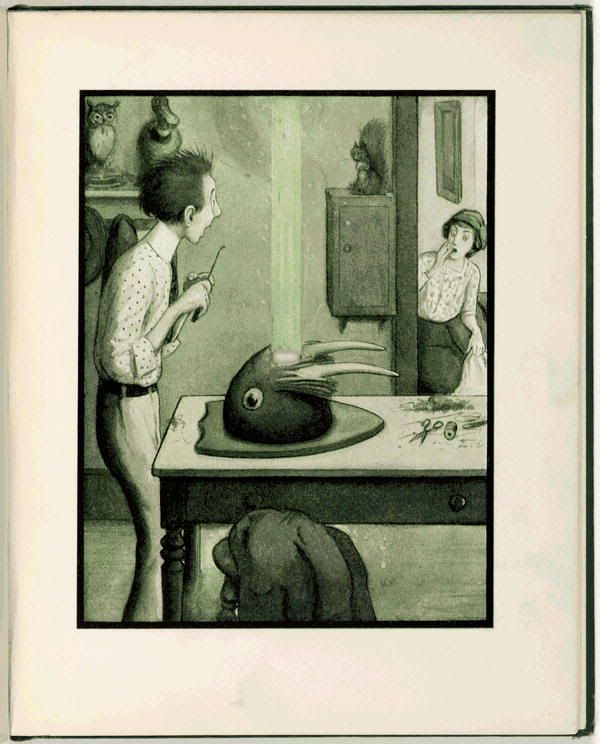

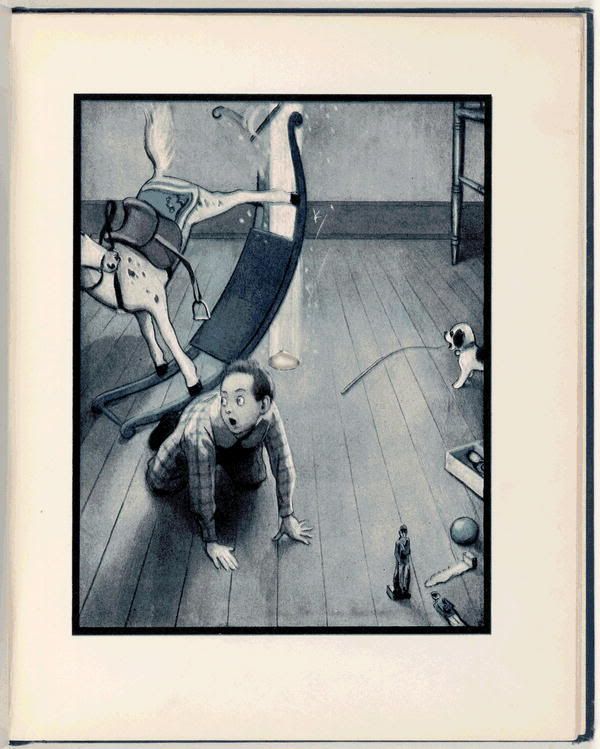

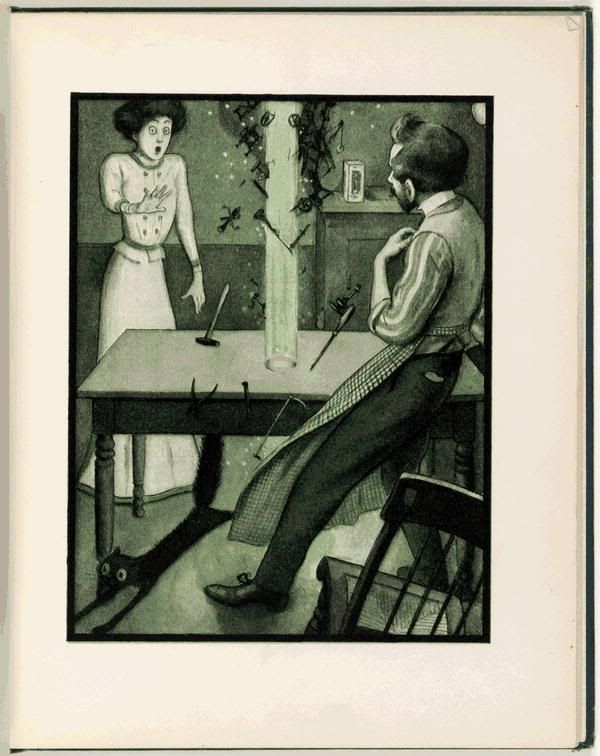

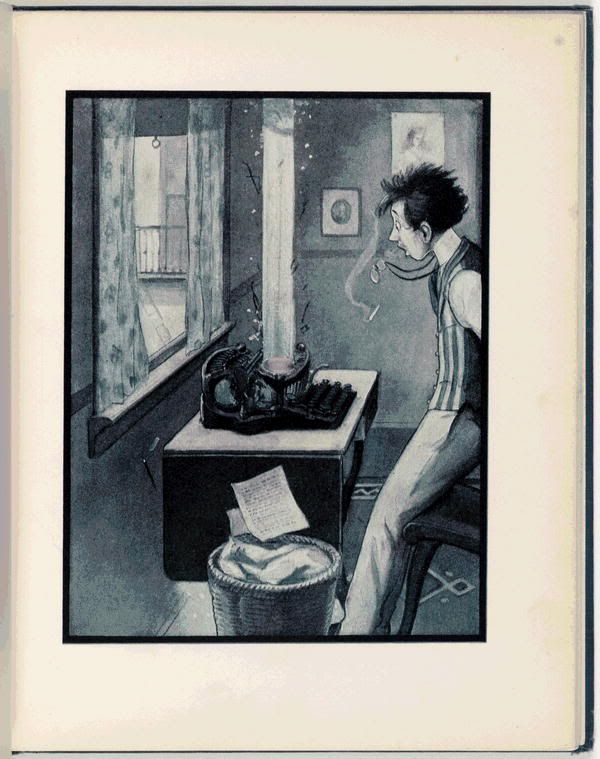

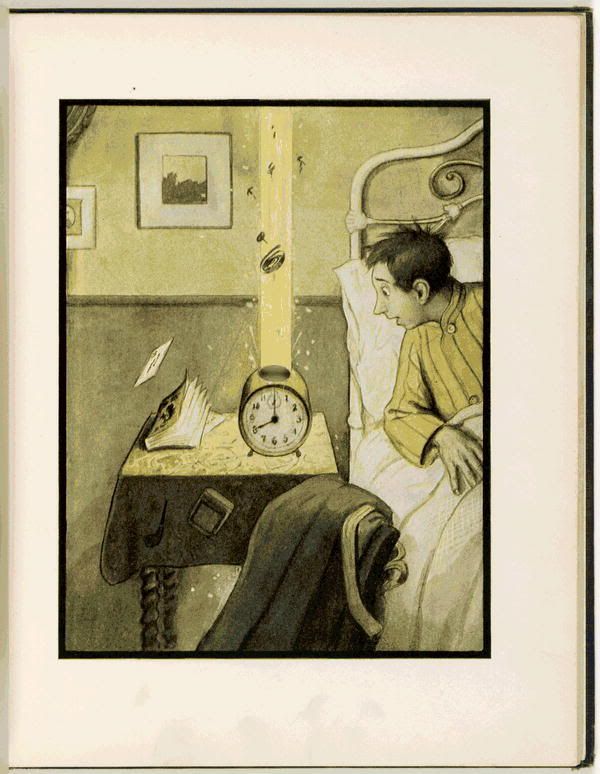

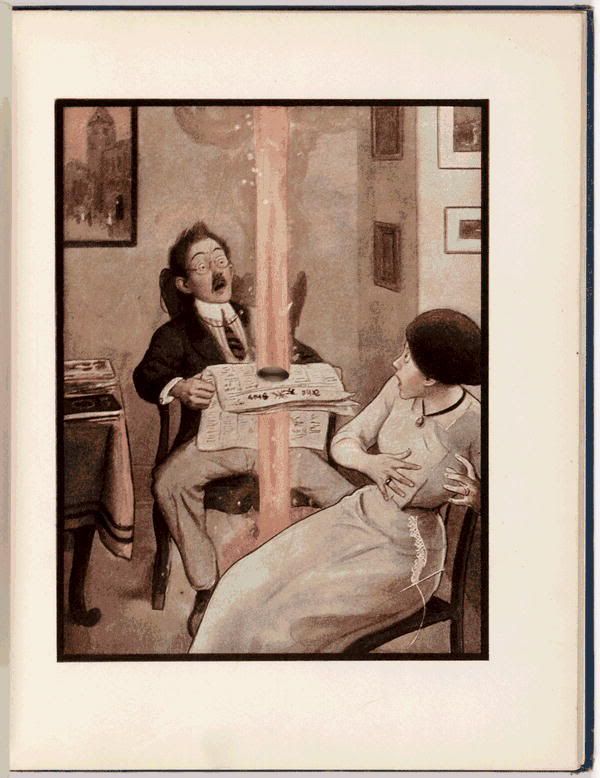

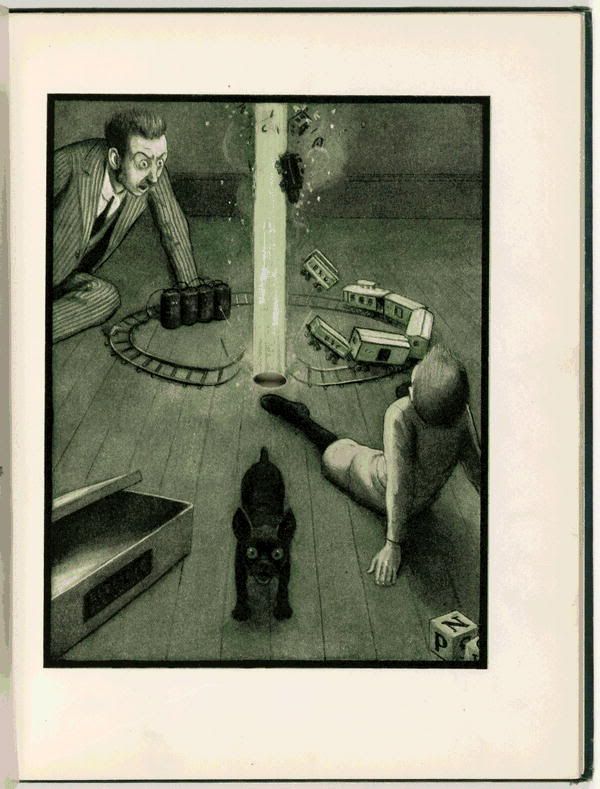

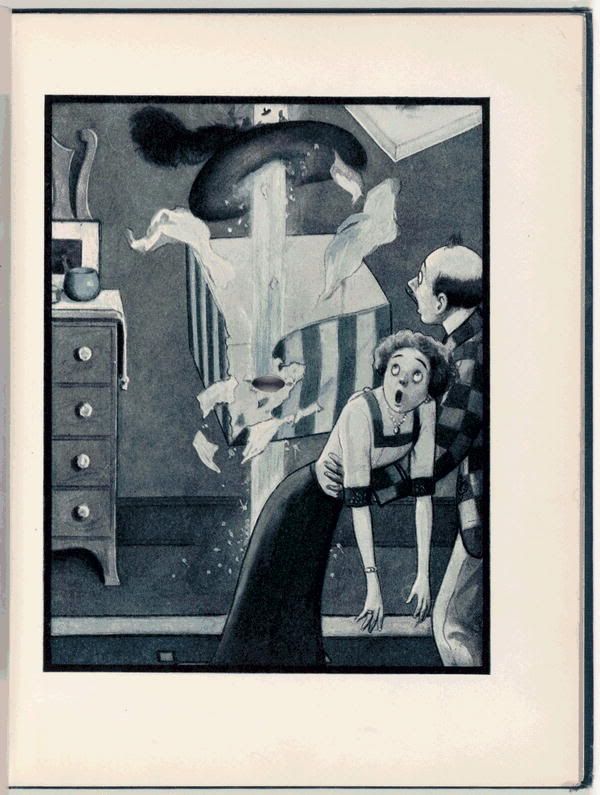

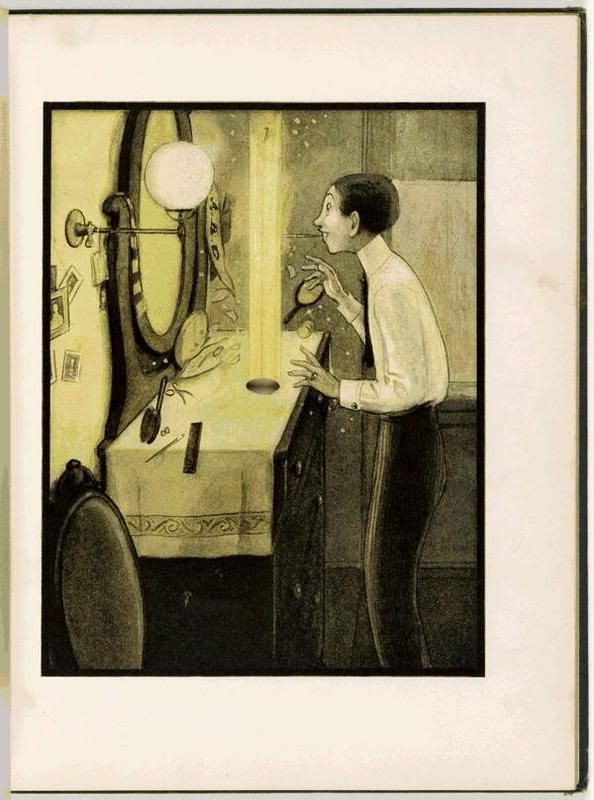

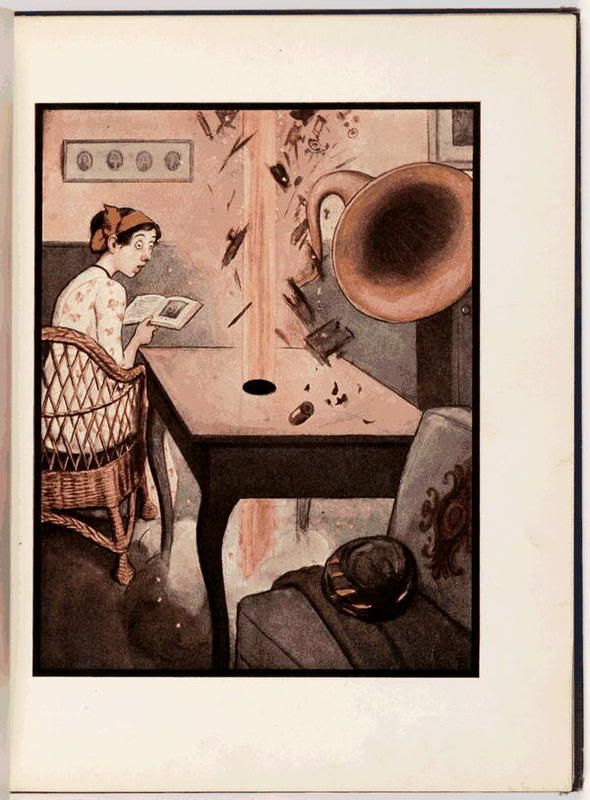

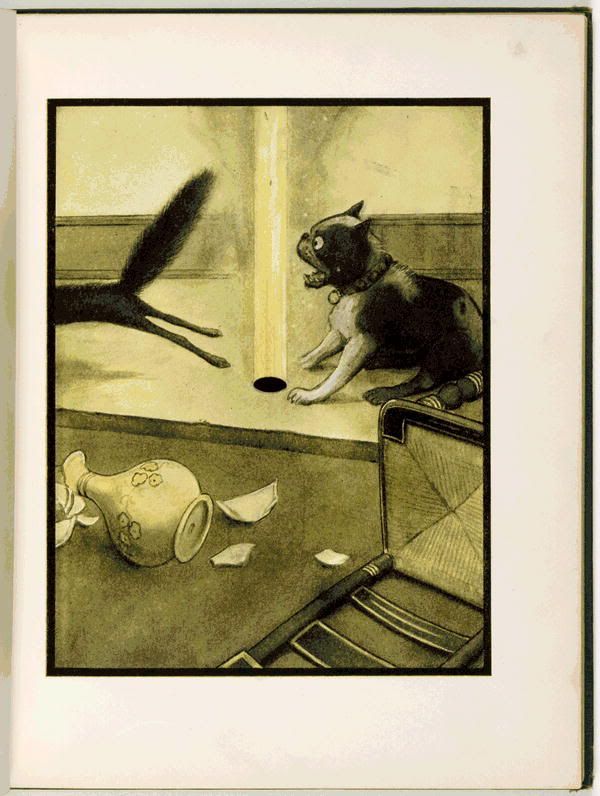

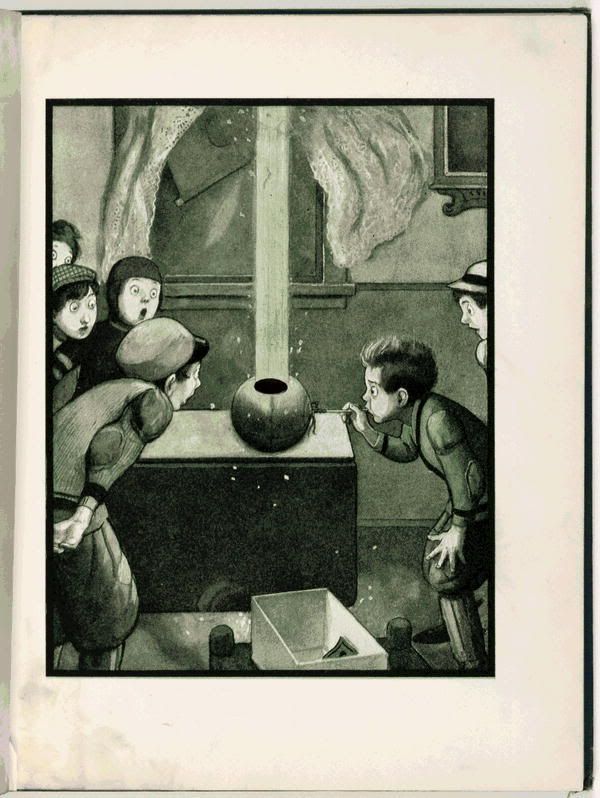

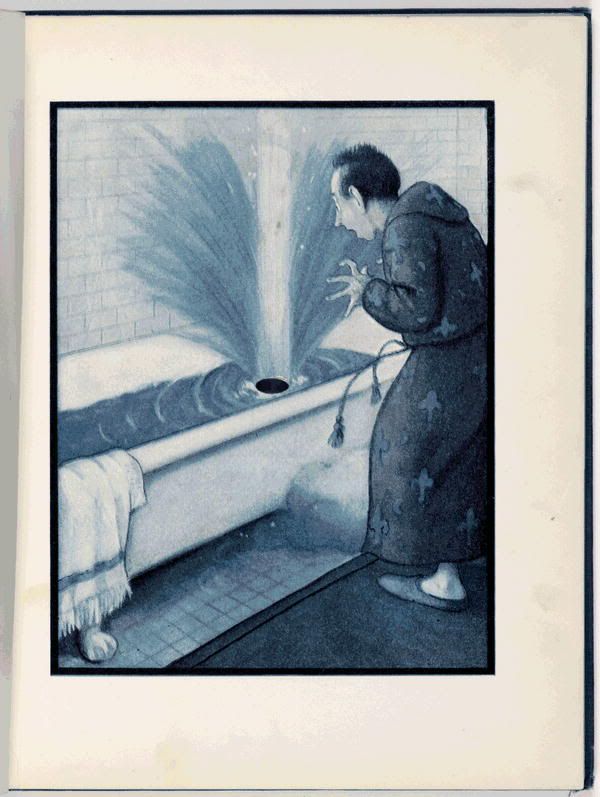

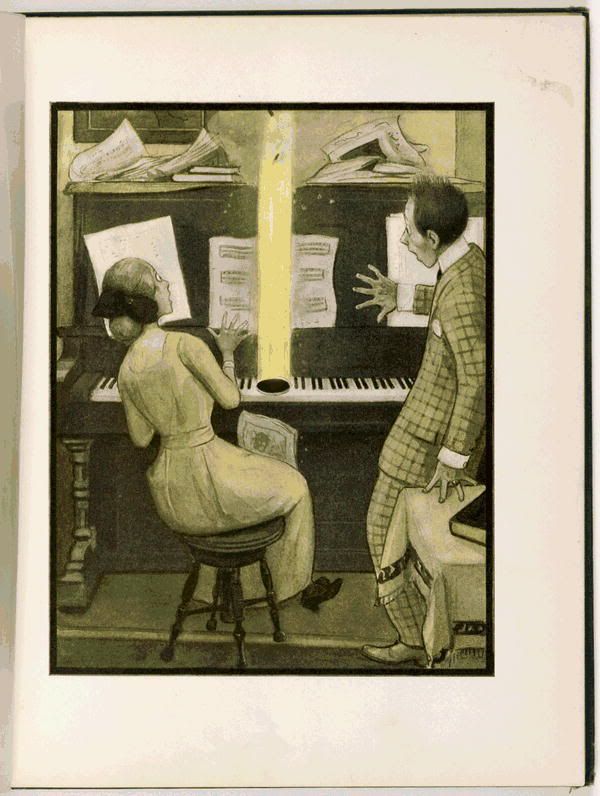

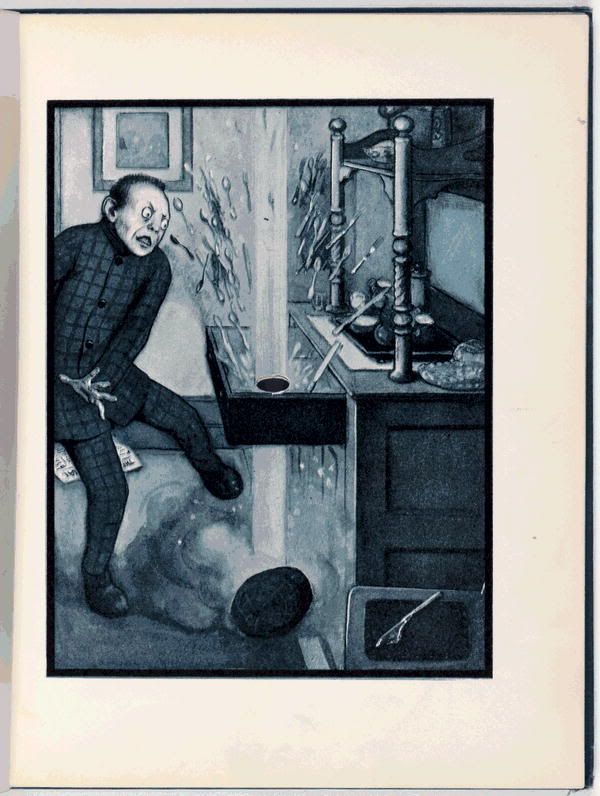

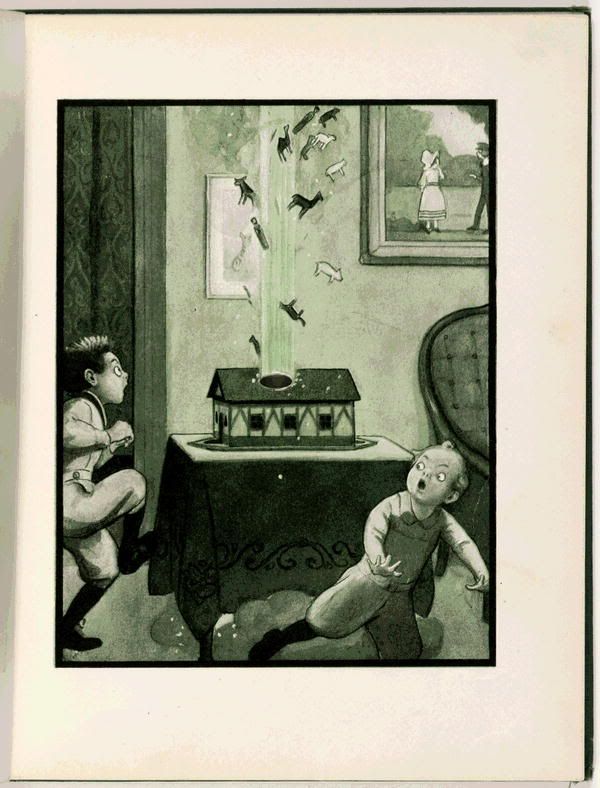

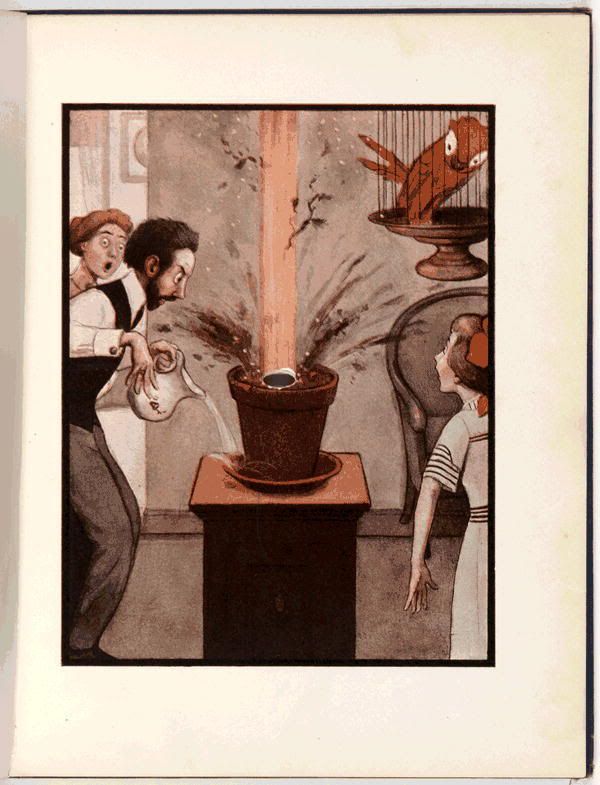

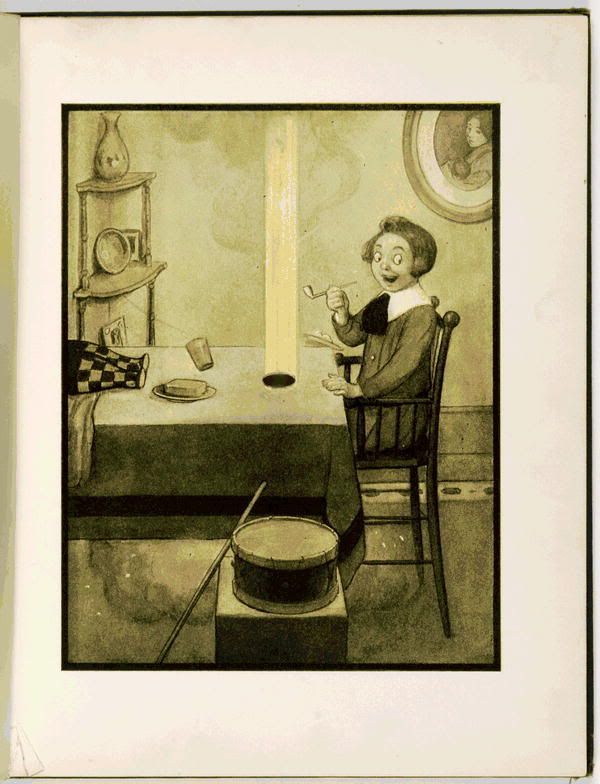

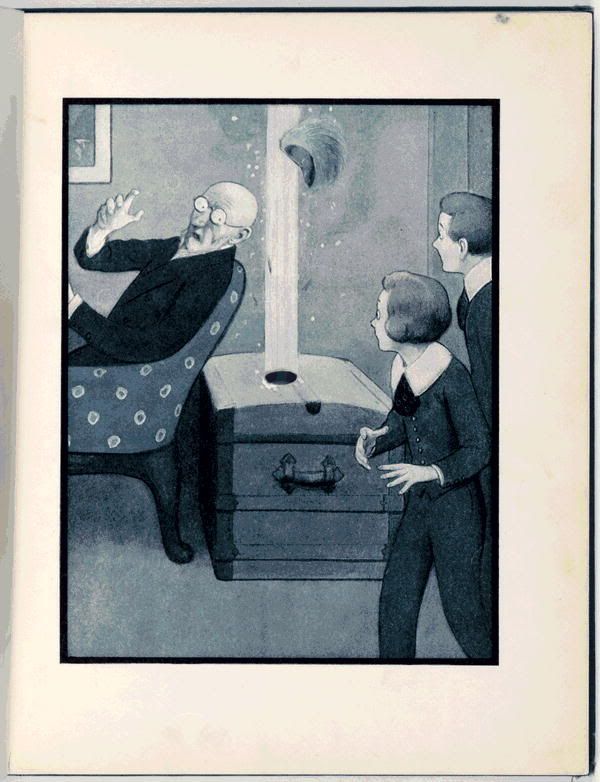

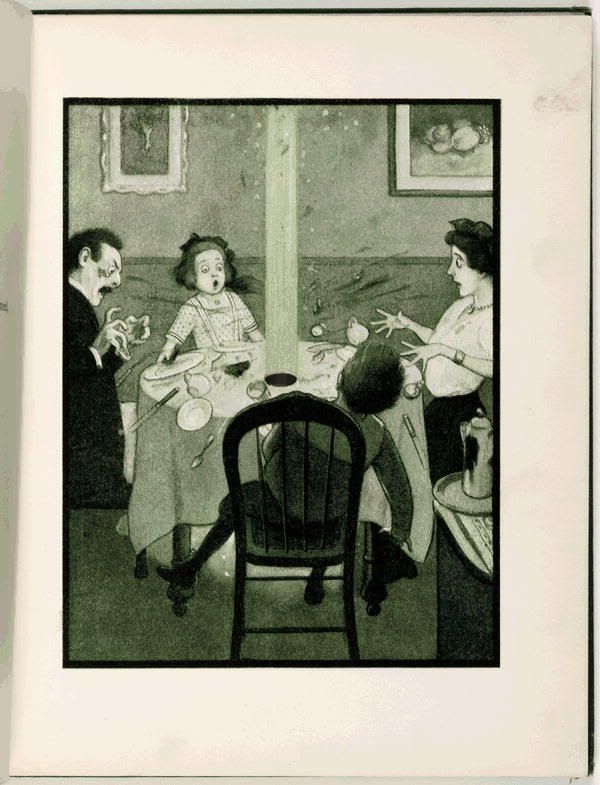

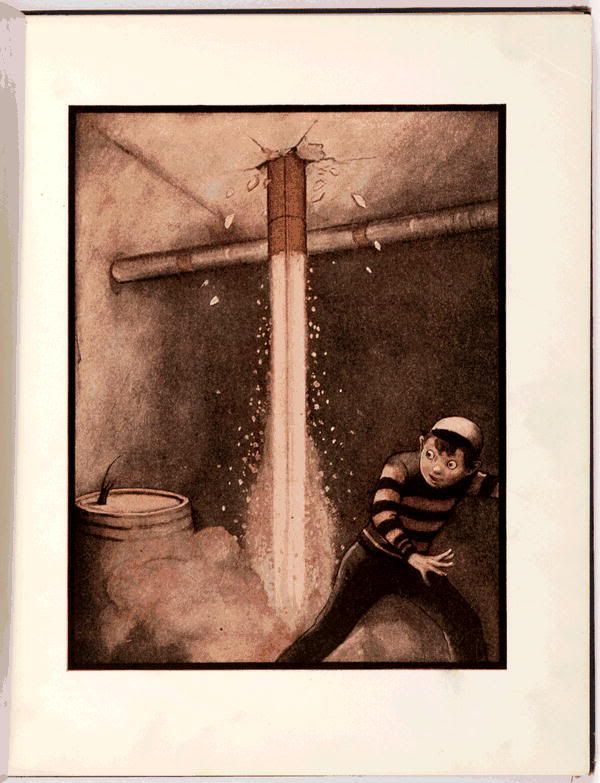

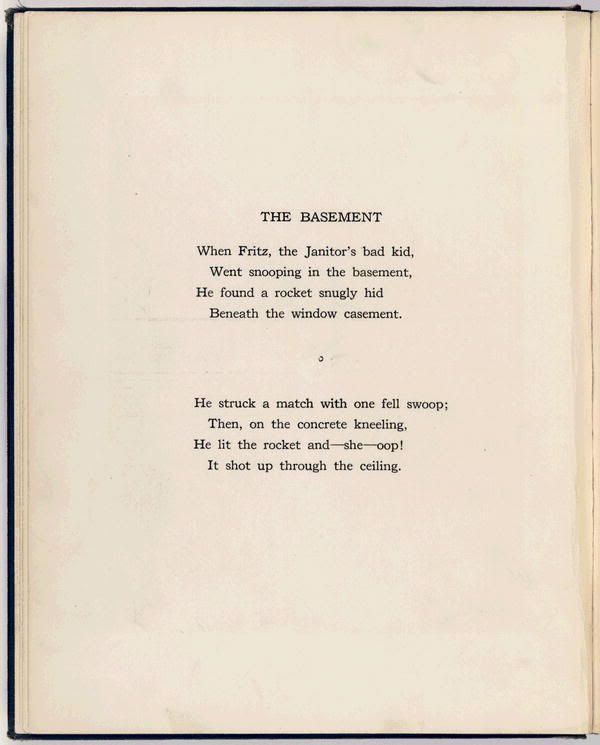

Reading this novel I thought, yes, this is what I want to do all the time. Why can't I just get paid to read books like this? I would be happy doing this indefinitely. Of course, are there books like this one? That is a harder question to answer. Tecumseh Sparrow Spivet (best. name. ever.) is a gifted prodigy in cartography at 12 years old. He lives on a ranch near Divide, Montana, with his mother, stalled entomologist, Dr. Clair, his teenage sister, Gracie, who would love to escape their small town and peculiar family, and strong-silent cowboy father T.E. Spivet. His brother Layton, has died, and we slowly learn more. T.S. keeps different coloured notebooks for maps of people doing things: zoological, geological, and topographical maps; and insect anatomy (should Dr. Clair ever call on his help), respectively. T.S. learns he has won the prestigious Baird Award from the Smithsonian, for his incredible mapping and scientific illustration work, and his adventure begins, as he decides to accept in person, but being 12, he sees his best means of transport as to hop on a freight train and hobo east. In this beautiful, whimsically illustrated book, T.S. maps everything from the Continental divide, to beetle subspecies, to cowboy moves, to facial expressions, to geology, to how McDonald's "penetrates my permeable barrier of aesthetic longing", to concentration of litter in Chicago, to his family history, to a many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics and what this might have meant for his family. This book is beautiful, in terms of the sensitivity and originality of the story (Wormholes of the Midwest! the hobo hotline?), the love of knowledge expressed, down to the layout of the text and images on the page. Maybe we will be lucky enough to be recruited into the Megatherium club. The manner in which this child's mind breaks up the world is a reminder of why science is wonderful and the joy of unfettered thinking. The story is also interwoven with that of T.S.' ancestors, including his great-grandmother the early geologist. We get both 'when science was young' and 'the young scientist'.

Maybe I'll go reread it myself now. (cross-posted to minouette)