|

The idea of the Music of the Spheres, like a symphony made by the motions of the cosmos is ancient. Sometimes Kepler is presented as a modern thinker who took the heliocentric Copernican model and placed it on a mathematical footing, correcting the circular orbits with ellipses (with our Sun at one focus). The truth is messier. Kepler started with music! Influenced by these mystical ideas, Kepler published Harmonices Mundi making his case that musical intervals and harmonies described the known planets and moon. He thought they made an inaudible harmony which could be heard by the soul. He also proposed that the planetary orbits were in the same proportions as a nested series of the five regular Platonic solids. His famous 3 laws of orbital motion were more of an afterthought and even then, he related angular speeds to musical intervals. The image is my Copernicus linocut with Kepler’s scales for planets and moon. |

In retelling the history of science it can often be presented as a series of facts or discoveries, sanitized of wrong turns, misleading presentations and striped of the story of how it was communicated to contemporaries. (I should point out that I'm not talking about how historians of science retell the history of science, but more everyone else). We rarely learn that the giants upon whose shoulders we stand were often also just lucky or got to the right answer for the wrong reasons or simultaneously believed some very strange, unsubstantiated things. There's a story to be told by the way thinkers and early scientists communicated their ideas to their contemporaries, and it's not a story which is well-known.

“Nature and Nature's laws lay hid in night:

God said, Let Newton be! and all was light.”

-Alexander Pope, 1688

It's occurred to me that basically, I'm railing against Pope, cause that's nonsense. Don't get me wrong. I'm a physicist by training. Newton's impact on physics and science broadly was tremendous. Newton's laws of motion, Newton's law of universal gravitation, and optics were genuinely revolutionary. But they didn't occur in a vacuum (no pun intended). Our knowledge of Newton's science is not due to his existence and the sudden consequential enlightenment for us all. Newton was a piece of work. We owe the publication of his grand book the Principia (1687) largely to the patience, diplomacy and determined persuasion of Edmond Halley (of comet fame) because otherwise, Newton might have taken much of his knowledge to the grave in a paranoid and antisocial fashion. Newton also had some very odd, arguably heretical religious and occultist beliefs and practised alchemy, which while it was a precursor of chemistry, was definitely filled with ideas that were not scientific and based on ideas about magic. Further, other scientists were working toward similar scientific ideas as Newton, which belies the lone genius myth. Robert Hooke (another real character) had deduced that gravitation was an inverse square law; the two argued over who had first made this discovery and I suspect Newton added Hooke to his long list of enemies. But even Newton acknowledged that Hooke and others knew the form of the law of gravitation by the 1660s. Halley himself had a weird and incorrect hollow Earth theory. We learn about Johannes Kepler's brilliant laws of planetary motion, building on Copernicus's heliocentric model, but it's rarely stressed that he came to his ideas not just through mathematics. It's not often that teachers point out that Kepler's model was based first on music and what frequencies of revolution would make nice harmonies if they were interpreted as notes and later on the proportions of regular Platonic solids, rather than simply trying to model Tycho Brahe's observations (though in his defence, it would decades before the long-awaited publication of the Principia, which would have provided him the tools needed). But my point being, this is not a story of confusion punctuated by insights which suddenly clear everything up. This is a much messier story.

I think we also often forget that a standard protocol of professional peer review scientific journals is quite recent. Scientific societies go back centuries, and did publish and otherwise disseminate scientific results but quality was mixed, and certainly influenced by biases like the sex, nationality, race, class and rank of the author. There was not a standard method for presenting results. Some discoveries were announced in letters to say, the Royal Society, which can be seen as an early precursor to scientific papers as we know them. Many early discoveries were presented in books. Something I find interesting is how they were combined with literature, in several instances, though not always without danger and risking accusations of heresy. Italian astronomer Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake after including some imaginative speculation with his science, arguing the universe is infinite and filled with innumerable potentially inhabitable worlds in 1600. Galileo presented his evidence supporting the Copernican model in 1632 in

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (

Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo) which is quite literally written as a dialogue between two philosophers and a layman. The staunch anti-Copernican follower of Ptolemy and Aristotle is name Simplicio as a broad hint to the reader! Galileo, like others including Hooke and Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens*, sometimes announced new results in an anagram, to establish priority

without actually revealing what they discovered! English clergyman and natural philosopher

John Wilkins wrote

The Discovery of a World in the Moone in 1638, inferring from the recent discovery of lunar mountains that it might also have inhabitants

. Jesuit scholar and polymath Athanasius Kirchner (who disagreed with Kepler and Galileo) wrote only two pieces of imaginative fiction, but one was a mystical dialogue about space travel between an angel and a narrator called

Itinerarium exstaticum in 1656. Huygens also wrote a book length speculation about extraterrestrial life,

Cosmotheoros, in Latin,

which he had published posthumously in 1698 for fear of censure (written partially as an annoyed response to Kirchner). It was translated in English as

The Celestial Worlds Discover'd. When Margaret Cavendish, the first and one of the only women who was able to attend a Royal Society meeting for centuries (as her wealth, rank and connections helped supersede the bias against her sex) and one of the first women to publish in her own name wrote

Observations upon Experimental Philosophy in 1666, she appended one of the earliest science fiction novels, a sort of imaginative complement to the science:

The Description of a New World, Called The Blazing-World, better known as The Blazing World, a fantasy, utopian satire. So with this sort of context, perhaps it makes sense that Kepler thought to try and write persuasively about his knowledge of lunar astronomy in the form of fiction, and in fact, an even earlier** example of science fiction.

Kepler wrote his Somnium (or The Dream) in 1608 and it was published posthumously in 1634 by his son. Its origin is even earlier. It harkens back to his frustrations with his dissertation of 1593 where he argued that an observer on the moon would see the Earth move just as we see the moon move from our frame of reference. But the Tübingen faculty, who disallowed new Copernican astronomy (and forced Kepler's mentor Maestlin to keep his thoughts to himself) vetoed debate on this idea. Kepler was able to graduate and continue with his career, but never forgot how this irked him. He eventually publishing a mystical combination of Aristotelian and Copernican astronomy called Mysterium Cosmographicum, which landed him a job with Danish astronomer and Imperial Mathematician to the Holy Roman Emperor, Tycho Brahe. Kepler inherited both Brahe's position but more importantly his unparalleled decades of observational data, which ultimately allowed him to deduce his law of ellipses published in his Astronomia Nova in 1609. Then his friend and ecclesiastical advisor to Emperor Rudolph, Wackher von Wackenfels asked him what he thought caused shadows on the moon. Unlike the Aristotelian Emperor who thought they were shadows of Earth's land masses, Kepler knew they were mountains and other geological features. Wackenfels encouraged Kepler to publish his own thoughts on this. So Kepler reimagined his thesis as Somnium, an imaginative story to get around the objections of the Aristotelians and to allow him to introduce a supernatural means of travelling to the moon to give him a reason to speculate about the lunar surface.

Like Cavendish, he inserts himself into the story, but only as a framing device. Also like Cavendish, his prose is pretty clunky. The plot of the story is that Kepler himself falls asleep, reading a book of legends, and has a dream. He dreams he's reading a book! The book tells of a young 14 year old Icelandic boy named Duracotus, being raised by his widowed mother Fiolxhilde, a wise woman who earns her living selling pouches of herbs to the sailors at port, as lucky charms with healing powers. The boy curiously cuts open a pouch and looses its contents. His mother sells him to the sailor in a fit of pique. Luckily for the boy, the sailor sails promptly to Denmark to deliver a letter to Tycho Brahe, who questions the boy, deems him clever, and decides to train him in astronomy, much to his delight. After five years, he takes his leave and returns home to find his mother had suffered after her rash decision and was overjoyed to see him. He tells her of his experience and training and she is thrilled. She reveals she has her own source of astronomical knowledge, the Daemon of Lavania, or spirit of the moon. Even more astonishingly, it is possible to travel to Lavania (the moon) with the Daemon's help and she proposes they both make the voyage. After sunset, she summons the Daemon and they make the voyage of "fifty thousand German miles" to the moon. This is about a factor of 5 too small, but it's the right order of magnitude and a decent estimate for the day.

The voyage is four hours and very difficult, and travellers are "hurled just as though he had been shot aloft by gunpowder to sail over mountains and seas," (to overcome what we now know is gravity) and thus are drugged with opiates to avoid shock. Damp sponges are used to allow them to breathe. The speed is so great the body instinctively rolls up and continues (due to what we now know as inertia) to move forward. They can only travel at the eclipse (notably a maximum of 4.5 hours, long enough for their 4 hour trip) to avoid the solar radiation in transit. The exhausted travellers are immediately brought to a cave, to shelter from the sun, and meet other daemons to learn about the moon's geography. This is an excuse for our author to basically dump all of his lunar astronomy knowledge so there's a long section of facts which don't advance the story as Kepler retells his thesis research. Then he describes a moon divided into Subvolva (which is below Volva, aka the Earth) and Privolva which never sees Volva (our far-side of the moon). Our moon is tidally-locked to the Earth so we only ever see one side. Kepler explains that the lunar day is a month of two weeks of scorching heat and two weeks of cold. He imagines the Earth, Volva, has a moderating effect on climate. He describes geography like our own but exaggerated with soaring mountains and plunging valleys. Likewise his imagined lifeforms are monstrous in size. He imagines nomadic Privolvans, some with legs larger than camels, or wings, following receding water in boats or diving under water (to survive the extremes of climate). Thus he's imagined intelligent extraterrestrials, which was a radical (and arguably heretical) idea in his time. He imagines Subvolvan like giant serpents wit spongy skin and animals shaped like pinecones. The story ends abruptly.

Kepler did not get the opportunity to publish this manuscript during his lifetime, but he did circulate it amongst friends. He lost control of the manuscript in 1611 and strangers, not up on the latest debates in science got access to it. Though he literally put himself into the story as the dreamer, readers saw the boy Duracotus trained by Tycho Brahe as a self-insert for Kepler. So they deduced that the fictional mother Fiolxhilde, wise woman and herb seller who communes with a demon, was a stand-in for Kepler's mother Katherine Kepler, an herbalist who was known to her neighbours for her vile temper, raised by an aunt, who had been burned as a witch. Ironically, it is really the Daemon of Lavania who is the voice of Kepler, revealing his lunar knowledge. By 1615, Katherine was arrested on suspicion of being a witch. Kepler's scheme to express his ideas and knowledge in fiction, to avoid the ire of the Aristotelians, had backfired badly, contributing to his mother getting caught up in the witch-craze. Kepler appreciated the danger and dropped all work to fight to exonerate his mother. The fight took 5 years, some of which she spent in prison, and the ordeal hastened her death two years later. Kepler felt culpable and her loss weighed on him. All of his work was set aside during this fight and publishing the Somnium in particular was out of the question. Over the last decade of his life he added 223 footnotes to the text, to insert most of the hard science. Having already faced such extreme consequences he no longer feared reprisals from Aristotelians. But, he died in 1630 with only 6 pages typeset. His son-in-law Jacob Bartsch took over, but he too died suddenly before it was published. Finally, his son Lucas published the book in an effort to help with his mother's financial distress. While not widely known today, the strange text casts has influenced science fiction and a marks one of the earliest scientific studies of an extraterrestrial planetary body.

*Huygens had his own dispute with Hooke over who invented the balance spring to regulate portable watches.

**But in my book, by no means the earliest. See for instance

A True Story by Lucian of Samosata (2nd century CE) which includes space exploration, aliens and interplanetary warfare - and which Kepler owned. There is also a near contemporary Copernican lunar science fiction story written by English historian

Francis Godwin (1562-1634),

The Man in the Moone, written in the 1620s and published 1638. Of course, clearly defining what counts as science fiction isn't entirely straightforward either.

References

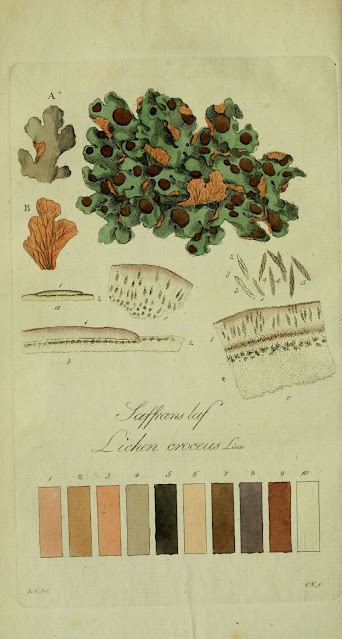

![Svenska lafvarnas färghistoria Stockholm :Tryckt hos C. Delén,1805-[1809] Svenska lafvarnas färghistoria Stockholm :Tryckt hos C. Delén,1805-[1809]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/a/AVvXsEhwJMIIpaeBuk7HzhSebtNw8BJ0R8W7ou1p_YpzhO3CQUZqFrO-9aMeEWjJU_eh-3gazSowFNfctjM8WDyDBxrc2Pu8uq-gFYLjJ6NbfQeaBC7ymw2QK8WeQgvailfccIrtuYdcAM8q-p0VyI0WpPmwg0DPvWQVzxcWAfGXy0ia7KYeYs5BzfT1GFE2=w344-h640)