Happy birthday Caroline Herschel! German-born Caroline Herschel (16 March 1750 – 9 January 1848), while overshadowed by her brother

William

(who discovered Uranus, amongst his other astronomical

accomplishments), was a real pioneer as a woman in astronomy and made

her own important contributions. In fact, she became the first salaried

female scientist, when King George III hired her to assist her

brother, at a time when there were few professional scientists

anywhere. Hers was a real life sort of Cinderella story, where rather

than marrying a prince, she made a life and career for herself.

Marriage was the expected role for a woman of her time, but she was

deemed unmarriageable, since a childhood bout of typhus stunted her

growth. Her mother thought she should train to be a servant, and

purposely stood in the way of her learning French, or music, to prevent

her from seeking employment as a governess. She wanted a perpetual

unpaid maid. Her father sometimes managed to include her in William's

lessons when their mother was absent. William had fled to England after

the Seven Years War and made a life as a musician and composer in Bath.

William managed to rescue his younger sister from their mother's

clutches, under the pretext that she might have the voice to be a solo

singer in Handel's oratorios, as she too was a natural musician. Of

course, he also wanted a woman to manage his bachelor household.

Meanwhile, he developed a real passion for astronomy. So, by the time

she arrived, all his spare time away from music was devoted to astronomy

and she found that despite her singing talent, she was roped into

assisting with the construction of telescopes, rather than receiving

music lessons. By 1781, William had discovered a new planet - Uranus ,

which he cannily dubbed the 'Georgian Star' after King George III. This

had the desired effect of securing himself a pension, so that he could

spend his time on astronomy (so long as he would present it to the King

when asked).

William and Caroline worked together at Slough, observing the night sky

with a variety of telescopes. William built some very large telescopes

and had Caroline take notes of what he observed, while she used

smaller 'sweeper' telescopes to sweep the skies for interesting object.

She discovered 11 nebulae (2 of which turned out to be galaxies) which

were previously unknown! She also found 8 or 9 comets, as well as

making and sharing observations of comets discovered by others. The

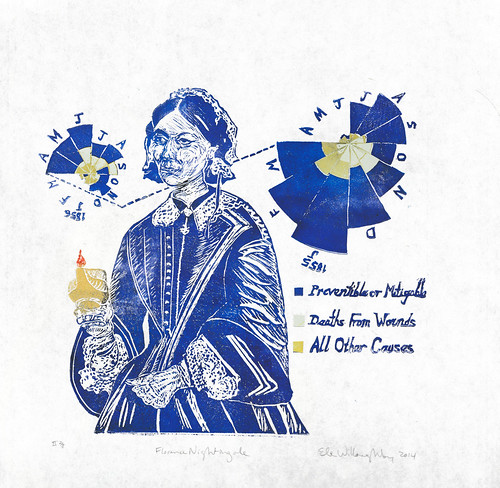

portrait is based on a miniature of Caroline, as well as her own notes

and diagrams from 1 August 1786, when she discovered her first comet,

now known as Comet C/1786 P1 (Herschel). On the left, her sketches of

the object "like a star out of focus" which she correctly identified as

a comet, is at the centre of the three circular diagrams labelled I,

II and III. On the right, her Fig I and Fig II show her observations

the following night, noting the position of the comet relative to the

constellations of Ursa Major and Coma Berenices.

She also independently re-discovered Comet Encke in 1795, first recorded by

Pierre Méchain in 1786. Later, in 1819, her observations help

Johann Franz Encke

recognize it was a periodic comet, like Halley's comet. Encke was able

to calculate its orbit, partially due to her observations. The comet

shown behind Caroline is based on a recent photo of Comet Encke, which

returns every 3 years.

In order to calculate orbits of newly discovered comets, it was

important to let other astronomers know as soon as possible. The letter

post was often not fast enough, if the weather turned cloudy. She

discovered her 8th comet while her brother was away. So, she took

matters into her own hands. After an hour's sleep, she saddled a horse,

and road the roughly twenty-six miles to the Greenwich Observatory of

the Astronomer Royal,

Nevil Maskelyne, much to his astonishment.

One of her important impacts on astronomy was that her early success

showed her brother how even an amateur using a small telescope could

find previously unobserved nebulae, and hence that there was real value

in making systematic sweeps of the night sky. Partnering together,

with William sweeping the sky with his 20 foot telescope and Caroline

taking notes by lamplight just inside the window, they went on to

discover 2507 nebulae and clusters over two decades of work. Further,

she acted as 'computer', doing the mathematical grunt work for her

brother's observations. William's study completely revolutionized

astronomy, and it couldn't have happened without Caroline's help.

They worked side by side nightly until 1788, when William married (at

age 49). Caroline was no longer needed to run his household, and he

offered her money as compensation. She, however, convinced him to

request her own salary from the King, which she received. She moved to a

cottage in the garden. She did a lot of her own observing for the next

nine years (while William was otherwise occupied at nights), and

gained more fame in her own right.

In 1797 the standard star catalogue used by astronomers was published by

John Flamsteed.

It was tough to use since it appeared in two volumes, with

discrepancies. William suggested that a proper cross-reference would be

a great help and a project for Caroline. She produced the resulting

Catalogue of Stars, published by the Royal Society in 1798. It

contained a index of all of Flamsteed's observed stars, all of the

errors in his volumes and a further 560 additional stars.

When William died in 1822, she returned to Hanover, where she was born,

but she continued her cataloguing and confirming of William's

observations. Her catalogue of nebulae aided her nephew

John Herschel

in his astronomical work. The Royal Astronomical Society presented her

with their Gold Medal in 1828 for this catalogue. She was the first

woman to receive the honour (and remained the only woman until Vera

Rubin in 1996).

She and

Mary Sommerville

were the first women admitted to the Royal Astronomical Society, when

they were elected Honorary Members in 1835. In 1838 she was elected an

honorary member of the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin. In 1846, at age

96 she also received a Gold Medal from the King of Prussia, for her

astronomical work (presented by none other than

Alexander von Humboldt). An asteroid and moon crater have been named in her honour.

You can find more in the great article on Caroline Herschel by Micheal Hoskin AAS Comittee on the Status of Women site (to which this blog post is indebted), Caroline Herschel's wikipedia entry, and the