|

| Nudibranch photographed by David Doubilet (via Photoshelter blog) |

Recently, I was tickled to read a tweet;

Oh god. Once you compare one dress with a nudibranch, they all look like Nudibranchs.

— Seelix Sparklefists (@seelix) January 12, 2015

For context, the Golden Globes were the previous evening.

|

| Ernst Haeckel, Kunstformen der Natur (1904), plate 43: Nudibranchia |

|

| Leopold and Rudolf Blashka, glass model of a nudibranch, late 19th/early 20th century |

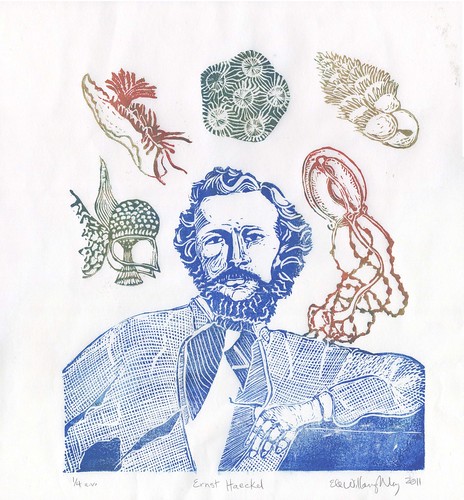

These spectacular marine invertebrates, are perhaps improbably, mollosks who shed their shells after the larval stage. They are multifarious and come in thousands of species, though they are often confused with sea slugs. You may have seen the illustrations by famed 19th century biologist and artist Ernst Haeckel (whom I've written about previously) or the amazing glass models of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka. They inhabit the all the oceans of the world. The come in every conceivable colour combination, it seems, a range of improbable shapes and though most are small they can range from roughly 1 to 50 cm in length like the fabulous Spanish Dancers. The name "nudibranch" comes from the Greek for "naked gill", a description of the rosette of branchial plumes protruding from their backs. The tentacles on their heads are sensitive to touch, taste, and smell. They are hermaphrodites, each having both types of sex organs, but they do need two to mate. They may appear harmless, but they are carnivores, and some produce and use toxins defensively. Even cannibalism is not unknown, and they will eat other species of nudibranch.

ré high fashion, they are sometimes their inspiration. Entire seasons for some designers may be inspired by sea creatures like the nudibranch.

|

| Mirella Bruno Print Design Project Direction Boards SS/2014. Note that this includes a few nudibranches. |

|

| Match #226 Yiqing Yin Fall 2012 | Jellyfishes at the Aquarium of The Bay in San Francisco, CA |

|

| Match #157 Jil Sander Spring 2011 | Jellyfish in a tank lit up with coloured lights photographed by pixelmama |

|

| Where I See Fashion: Match #1 gown and jellyfish |

|

| Where I See Fashion Match #8 photo and bioluminescent jellyfish |

So, without further ado, and with thanks to all the people and creatures mentioned for their inspiration, here are my Oscar dress/Nudibranch pairs:

|

| Marion Cottilard attends the 87th Annual Academy Awards, February 22, 2015 (MARK RALSTON/AFP/Getty Images) and dorid nudibranch Cadlina luteomarginata (Jeff Goddard, Santa Barbara). |

|

| Rosamund Pike attends the 87th Annual Academy Awards, February 22, 2015 (Photo by Jeff Vespa/WireImage) and a spanish dancer nudibranch off Australia (Photoe by Chris, Underwater Australia) |

|

| Emma Stone (Getty) and Manned Nudibranch Aeolidia papillosa (Photo (c) Luc Gangnon, 2015 Aquatic Biodiversity Monitoring Network) |

|

| Blanca Blanco (Getty) and nudibranch (via here) |

|

| Scarlett Johansson (Mark Raulston/AFP/Getty) and green nudibranch (by Saffron on scuba-fish gallery) |

|

| Gwenyth Paltrow (Getty) and a Nudibranch egg rosette |