|

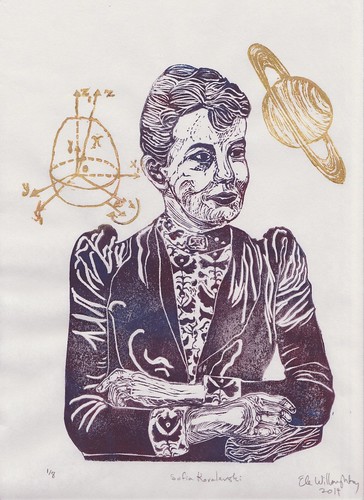

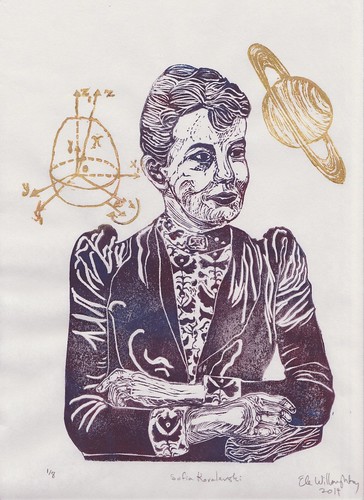

| 'Sofia Kovalevski', linocut 9.25" by 12.5" (23.5 cm by 32 cm), 2014 by Ele Willoughby |

Today is the birthday of the great Russian mathematician and writer,

Sofia Vasilyevna Kovalevski (1850-1891), in honour of which, I'm going to make the first of a series of posts about scientists I've portrayed.

Also known as Sofie or Sonya, her last name has been transliterated from

the Cyrillic Со́фья Васи́льевна Ковале́вска in a variety of ways,

including Kovalevskaya and Kowalevski. Sofia's contributions to

analysis, differential equations and mechanics include the

Cauchy-Kovalevski theorem and the famed Kovalevski top (well, famed in

certain circles, no pun intended). She was the first woman appointed to a

full professorship in Northern Europe or to serve as editor of a major

scientific journal. She is also remembered for her contributions to

Russian literature. All of this despite living when women were still

barred from attending university. Her accomplishments were tremendous in

her short but astonishing life.

Born Sofia Korvin-Krukovskaya,

in Moscow, the second of three children,

she attributed her early

aptitude for calculus to a shortage of wallpaper, which lead her father

to have the nursery papered with his old differential and integral

analysis notes. Her parents nurtured her early interest in math, and

hired her a tutor. The local priest's son introduced her to nihilism. So

both her bent for revolutionary politics and passion for math were

established early.

Unable to continue her education in Russia,

like many of her fellow modern, young women including her sister, she

sought a marriage of convenience. Women were both unable to study at

university or leave the country without permission of their father or

husband. Men sympathetic to their plight would participate in

"fictitious marriages" to allow them an opportunity to seek further

education abroad. She married the young paleontology student, Vladimir

Kovalevsky, later famous for his collaboration with Charles Darwin. They

emigrated in 1867, and by 1869 she enrolled in the German University of

Heidelburg, where she could at least audit classes with the professors'

permission. She studied with such luminaries as Helmholtz, Kirchhoff

and Bunsen. She moved to Berlin and studied privately with Weierstrass,

as women could not even audit classes there. In 1874, she present three

papers, on partial differential equations, on the dynamics of Saturn's

rings (as illustrated in my linocut) and on elliptic integrals as a

doctoral dissertation at the University of of Göttingen. Weierstrass

campaigned to allow her to defend her doctorate without usual required

lectures and examinations, arguing that each of these papers warranted a

doctorate, and she graduated summa cum laude - the first woman in

Germany to do so.

She and her husband counted amongst their

friends the great intellectuals of the day including Fyodor Dosteyevsky

(who had been engaged to her sister Ann), Thomas Huxley, Charles Darwin,

Herbert Spencer, and George Elliot. The sentence "In short, woman was a

problem which, since Mr. Brooke's mind felt blank before it, could

hardly be less complicated than the revolutions of an irregular solid."

from Elliot's Middlemarch, is undoubtedly due to her friendship with

Kovaleski. Sofia and Vladimir believed in ideas of utopian socialism and

traveled to Paris to help those the injured from the Paris Commune and

help rescue Sofia's brother-in-law, Ann's husband Victor Jaclard.

In

the 1880s, Sofia and her husband had financial difficulties and a

complex relationship. As a woman Sofia was prevented from lecturing in

mathematics, even as a volunteer. Vladimir tried working in business and

then house building, with Sofia's assistance, to remain solvent. They

were unsuccessful and went bankrupt. They reestablished themselves when

Vladimir secured a job. Sofia occupied herself helping her neighbours to

electrify street lamps. They tried returning to Russia, where their

political beliefs interfered with any chance to obtain professorships.

They moved on to Germany, where Vladimir's mental health suffered and

they were often separated. Then, for several years, they lived a real

marriage, rather than one of convenience, and they conceived their

daughter Sofia, called Fufa. When Fufa turned one, Sofia entrusted her

to her sister so she could return to mathematics, leaving Vladimir

behind. By 1883, he faced increasing mood swings and the threat of

prosecution for his role in a stock swindle. He took his own life.

Mathematician

Gösta Mittag-Leffler, a fellow student of Weierstrass, helped Sofia

secure a position as a privat-docent at Stockholm University in Sweden.

She developed an intimate "romantic friendship" with his sister,

actress, novelist, and playwright Duchess Anne-Charlotte Edgren-Leffler,

with whom she collaborated in works of literature, for the remainder of

her too short life. In 1884 she was appointed "Professor

Extraordinarius" (Professor without Chair) and became the editor of the

journal Acta Mathematica. She won the Prix Bordin of the French Academy

of Science, for her work on the rotation of irregular solids about a

fixed point (as illustrated by the diagram in my linocut) including the

discovery of the celebrated "Kovalevsky top". We now know there are only

three fully integrable cases of rigid body motion and her solution

ranks with those of mathematical luminaries Euler and Lagrange. In 1889,

she was promoted to Professor Ordinarius (Professorial Chair holder)

becoming the first woman to hold such a position at a northern European

university. Though she never secured a Russian professorship, the

Russian Academy of Sciences granted her a Chair, after much lobbying and

rule-changing on her behalf.

Her writings include the memoir A

Russian Childhood, plays written in collaboration with Edgren-Leffler,

and the semi-autobiographical novel Nihilist Girl (1890).

Tragically,

she died at 41, of influenza during the pandemic. Prizes, lectures and a

moon crater have been named in her honour. She appears in film and

fiction, including Nobel laureate Alice Munro's beautiful novella 'Too

Much Happiness', a title taken from Sofia's own writing about her life.

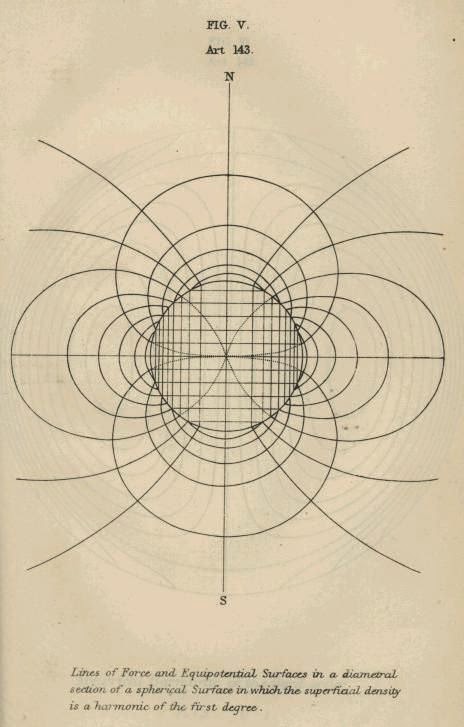

from Lectures on Ventilation (1869) by Lewis W. Leeds.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.