Quantum mechanics is the physics of the very small, the subatomic. On that scale classical physics we know intuitively, the physics of our everyday life and human-sized things, breaks down. Strange things can happen; objects (or wave-particles at least) can go through walls or seem to go through two different French doors at the same time. We can't investigate this world without literally interfering with it. We can only know something's position or momentum precisely; it's either where or how fast, but not both. We can only meaningfully make predictions about groups of things: half of these radioactive nuclei will decay in one half-life; the electrons going through these two slits will make this specific interference pattern, but don't ask me to explain what any individual electron will do, and so forth. This sort of anti-intuitive arena inspires either purely mathematical and probabilistic or very metaphorical descriptions. Some things are unknowable, based on the fundamental laws of physics. Working in this Wonderland and believing seven impossible things before breakfast can inspire creativity and often visual thinking in physicists. This weird world within is also a source of inspiration to visual artists.

One of the most amazing and distinctly visual tools in the quantum mechanic's tool box is the

Feynman diagram. These elegant schematics of lines and assorted squiggles not only depict the sorts of things which can occur in any given interaction in the quantum world, they actually allow us to calculate probabilities; they actually represent and take the place of complex equations - and believe you me are far easier to work with. Everyone would rather draw a series of little drawings than calculate probability amplitudes by integrating over many variables. They are quite easy to read, once you know the vocabulary of particles, antiparticles, force carriers - real and virtual - and they can describe everything which can occur in the quantum world. It's perhaps no surprise that preeminent information designer and champion of elegance, simplicity and meaning in scientific graphics,

Edward Tufte would be inspired to creature sculptures of Feynman diagrams with stainless steel tubing.

|

| Richard Feynman, Equations and Sketches, 1985 |

|

Feynman himself of course had an artistic side. It is well-known that he played the bongos, or painted some of his own diagrams on his van. You may have heard his 'Ode to a flower' - a beautiful refutation of the bias that beauty is to only be found in art, and it is lost on science. The short monologue is animated by Fraser Davison below. He himself started to draw, at age 44, shortly after developing his visual language for quantum mechanics (via

Brain Pickings). He traded art for science lessons with his friend the doubter that scientists could see the beauty of a flower. His daughter Michelle even gathered his drawings into a short book

The Art of Richard P. Feynman: Images by a Curious Character.

Richard Feynman - Ode To A Flower from

Fraser Davidson on

Vimeo.

|

| Oliver Jeffers, 'Still life with light and lightbulb' |

Painter and illustrator Oliver Jeffers got inspired by quantum mechanics, and wave-particle duality. As he himself explains below, we find that if you set up and experiment to look for a wave, light (and in fact electrons, or other quantum wave/particles) will behave like a wave; whereas, if you set up an experiment to look for a particle light (and other wavicles) will behave like a particle. His painting 'Still life with light and lightbulb' includes the

de Broglie equation, relating wavelength to momentum of anything! (So particles, with mass and momentum have wavelengths, and photons which can seem like waves have momentum like particles).

|

Julian Voss-Andreae, The Well (Quantum Corral), 2009

Gilded wood, 3” x 13” x 12” x (6 x 34 x 31 cm) |

Julian Voss-Andreae is a sculptor who also pursued graduate research in quantum mechanics. His background comes out in his sculptures of 'Quantum Objects' and molecular structures. A quantum coral is a a ring of atoms arranged in an arbitrary shape on a substrate. Lutz, Eigler and Crommie (1993), for instance used a ring of iron (which is ferromagnetic) atoms on copper to reflect the surface electrons into a predicted wave pattern - 'coralling' them into the 'fence' of iron. Voss-Andreae used their specific data to create his sculpture The Well (as in a quantum mechanical well or potential energy well in which electrons are trapped). Like any wavicle, the nature of his 'Quantum Man' sculpture depends on how you look at it, appearing quite solid or nearly disappearing altogether. He also makes beautiful sculptures of structures right at the classic/quantum interface... where the weird world of the very small gets to sufficiently large molecular structures to obey the physics of our everyday world, like 'Quantum Buckeyball' and the many complex protein molecules. His graduate work incidentally, showed that single object as large as Carbon-60, a Buckyball, would behave like a wave, going through two slits at once (just like electrons in the famous

double slit experiment).

|

| Julian Voss-Andreae, Quantum Man |

|

| Julian Voss-Andreae, Quantum Buckeyball |

|

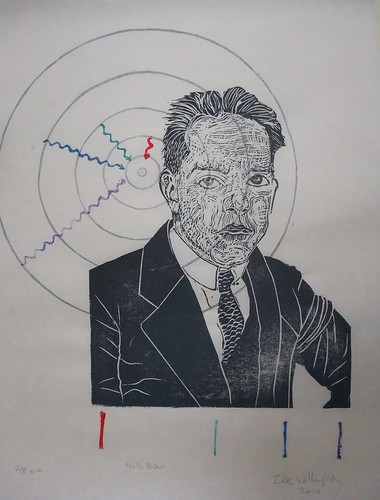

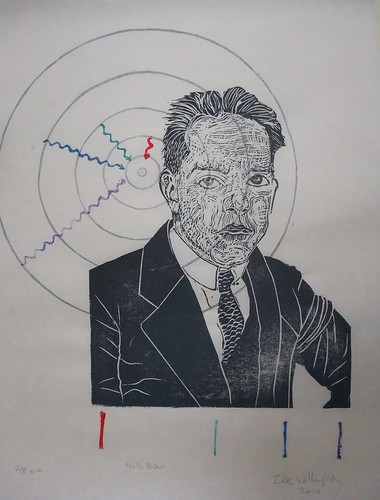

| Ele Willoughby, Niels Bohr, 2010 |

My own artwork on the subject of quantum mechanics is a little less literal perhaps... though my linocut portrait of

Niels Bohr includes the

Bohr model explanation of the

Balmer series - the spectral lines given off by excited hydrogen which are in the visible range, showing Bohr's electron orbits (which we now know are a bit too simplistic a model) at the right ratio of diameters, and photons (shown as wavy lines, following Feynman's convention) given off as an electron falls from one given orbit to another lower energy state in the appropriate colours. The line spectrum you would see, if you spread the light given off with a prism, is shown below. I've also depicted

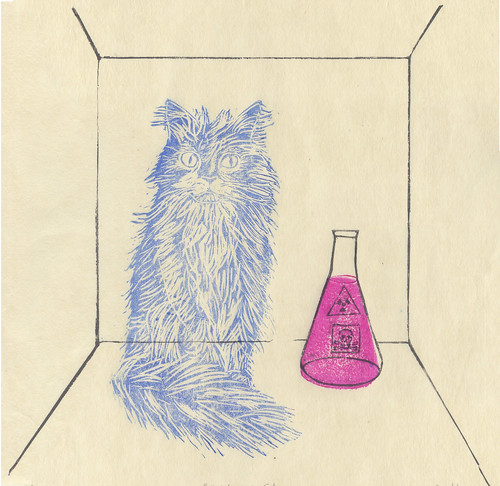

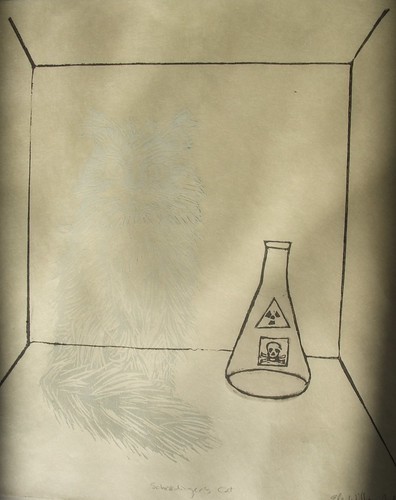

Schrödinger's cat, one of the most famous thought experiments (or, really metaphors for the weirdness of quantum mechanics).

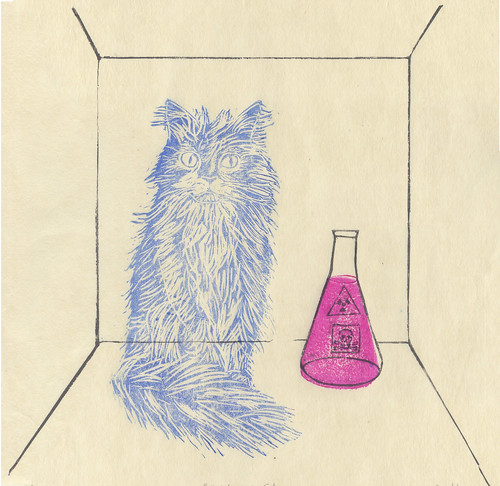

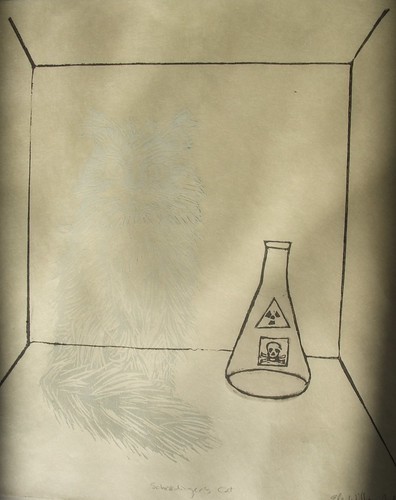

Erwin Schrödinger proposed this hypothetical experiment to link the strangeness of the quantum world to our everyday world of big things like cats. He imagined a cat in a box with a vial of lethal poison which would rupture if and only if a radioactive particle had decayed - an individually unpredictable quantum event. Until you open the box, is the cat dead or alive? According to quantum mechanics, the wavefunction (or equation describing its state) is the superposition of that of dead and live cat... that is, equal parts live and dead... which of course, seems absurd. Whether the cat is alive or dead depends on when you look at it. Hence, I made a cat and poison vial in thermochromic temperature-dependant ink; sometimes they are apparent, sometimes they are not (or at least, it's too warm and they turn colourless).

|

| Ele Willoughby, Schrödinger's Cat (coloured state), 2011 |

|

| Ele Willoughby, Schrödinger's Cat (colourless state) |

Length: 205mm.